Executive Summary

Credit card rewards programs have become a fixture in consumer finance, offering incentives like cash back, points, and travel miles. This thought experiment explores credit card rewards as a mechanism of social engineering, delving into their psychological, neurological, economic, and ethical implications.

My analysis uncovers how these programs harness behavioral economics and cognitive psychology principles to shape consumer behavior. By leveraging psychological triggers such as operant conditioning, loss aversion, and cognitive biases, they drive increased usage and spending. Neuroimaging research highlights that the anticipation and reception of rewards activate the brain’s dopamine-fueled reward pathways, reinforcing usage patterns.

Economically, credit card rewards influence consumer spending and debt trends. While some consumers effectively benefit, evidence suggests a redistribution of costs to less savvy users or those unable to maximize their rewards. Credit card issuers employ increasingly sophisticated marketing strategies, integrating personalization and gamification to deepen engagement.

The regulatory environment for credit card rewards is multifaceted, marked by ongoing debates on consumer protection and financial literacy. As payment technologies advance, these programs may become more entwined with new financial products and services.

This discussion concludes that, despite tangible benefits for many users, credit card rewards pose critical questions regarding consumer welfare, financial choices, and the ethical duties of financial institutions. Continued research, regulatory oversight, and public discussion are vital to ensure these programs serve broader societal interests.

Introduction

Credit card rewards programs have become an integral part of the financial landscape, offering consumers a variety of incentives for their spending. These programs, which typically provide cash back, points, or miles, have evolved significantly since their inception in the 1980s [1]. Today, they represent a powerful tool for financial institutions to attract and retain customers, while simultaneously influencing consumer behavior in ways that extend far beyond simple transactional relationships.

Brief history of credit card rewards

The concept of credit card rewards can be traced back to 1984 when Diners Club introduced the first airline miles program [2]. This innovation quickly spread across the industry, with American Express launching Membership Rewards in 1991 and major banks following suit throughout the 1990s and 2000s [3]. Over time, these programs have become increasingly sophisticated, offering a wide range of redemption options and tailored benefits to suit different consumer segments.

Definition of social engineering in this context

In the context of this discussion, I define social engineering as a deliberate attempt to influence human behavior and decision-making through the design and implementation of systems, policies, or incentives. When applied to credit card rewards, social engineering refers to the ways in which these programs are structured to shape consumer spending habits, financial decisions, and even lifestyle choices [4].

This post aims to provide an analysis of how credit card rewards function as a form of social engineering, examining the psychological mechanisms at play, the neurological basis for their effectiveness, their economic impacts, and the ethical considerations they raise. By synthesizing research from various disciplines, I seek to offer some nuance to the understanding of these programs and their broader societal implications.

Psychological Mechanisms

Credit card rewards programs leverage several key psychological principles to influence consumer behavior. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for comprehending the effectiveness of these programs as tools for social engineering.

Operant conditioning and reward reinforcement

At its core, the psychology of credit card rewards is rooted in the principles of operant conditioning, a concept developed by B.F. Skinner [5]. In this context, the rewards act as positive reinforcement for credit card usage. Each time a consumer makes a purchase and receives a reward (e.g., cash back or points), it strengthens the association between the behavior (using the credit card) and the positive outcome (receiving rewards) [6].

This reinforcement is particularly effective due to its variable ratio schedule. Consumers don’t receive rewards for every single transaction, and the value of rewards can vary, creating a pattern of reinforcement similar to that found in gambling, which is known to be highly effective in maintaining behavior [7].

Loss aversion and the endowment effect

Loss aversion, a key concept in behavioral economics, posits that people are more sensitive to losses than to equivalent gains [8]. Credit card rewards programs exploit this tendency by framing unused rewards as potential losses. Once consumers accumulate rewards, the endowment effect comes into play, causing them to value these rewards more highly simply because they possess them.

This psychological attachment to accumulated rewards can lead consumers to make decisions they might not otherwise make, such as increasing their spending to reach reward thresholds or maintaining cards with annual fees to avoid “losing” their rewards.

Cognitive biases relevant to credit card usage

Several cognitive biases play significant roles in how consumers interact with credit card rewards:

- Present bias: Consumers tend to overvalue immediate rewards compared to future costs, leading to increased spending and potential debt accumulation.

- Optimism bias: Many cardholders overestimate their ability to pay off balances and underestimate the likelihood of incurring interest charges, making reward cards seem more attractive than they may be.

- Choice overload: The complexity of many rewards programs can lead to decision paralysis or suboptimal choices, as consumers struggle to compare different offerings.

- Anchoring: Initial reward offers, or spending thresholds can serve as anchors, influencing consumers’ perceptions of value and spending decisions.

- Mental accounting: Consumers often treat rewards as “free money,” leading to increased spending or less careful financial decision-making when using rewards for purchases.

Understanding these psychological mechanisms provides insight into why credit card rewards programs are so effective at influencing consumer behavior, often in ways that may not align with individuals’ long-term financial interests.

Neurological Basis

The effectiveness of credit card rewards programs is not only rooted in psychological principles but also has a neurological basis. Advances in neuroscience have provided insights into how these rewards affect brain function and decision-making processes.

Brain reward systems and dopamine

Credit card rewards activate the brain’s reward system, primarily through the neurotransmitter dopamine. This system, which includes structures such as the nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, and prefrontal cortex, plays a crucial role in motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement learning.

When individuals anticipate or receive rewards from credit card usage, dopamine is released in these brain regions. This neurochemical response creates a sense of pleasure and reinforces the behavior that led to the reward. Over time, this can lead to the formation of habitual credit card usage patterns, as the brain learns to associate card use with positive outcomes.

Research has shown that the dopamine response to rewards can be particularly strong when the rewards are uncertain or variable, which is often the case with credit card rewards programs that offer different levels of rewards for different categories of spending or during promotional periods.

Neuroimaging studies on credit card usage

Several neuroimaging studies have provided direct evidence of how credit card rewards affect brain activity:

- A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study by Knutson et al. (2007) found that anticipation of monetary gains activated the nucleus accumbens, a key component of the brain’s reward system. This activation was observed when participants were presented with credit card cues, suggesting that merely thinking about using a credit card can trigger reward-related neural responses.

- Another fMRI study by Prelec and Simester (2001) demonstrated that credit card cues activated brain regions associated with reward processing more strongly than cash cues, even when the monetary amounts were identical. This suggests that credit cards may be inherently more rewarding at a neural level than cash transactions.

- Research by Ceravolo et al. (2019) using electroencephalography (EEG) found that credit card rewards modulated neural responses to purchasing decisions, with enhanced activity in regions associated with reward processing when participants made purchases that earned rewards.

- A study utilizing positron emission tomography (PET) by Volkow et al. (2002) showed that dopamine release in the striatum correlated with the subjective experience of reward anticipation. This finding has implications for understanding how the anticipation of credit card rewards might influence decision-making processes.

These neuroimaging findings provide a biological basis for understanding why credit card rewards can be so compelling. The activation of reward-related brain regions and the release of dopamine create a powerful neurological incentive for continued credit card usage, potentially overriding more rational decision-making processes.

Furthermore, research in neuroeconomics has shown that the brain’s reward system is involved in value-based decision-making. This suggests that the neurological responses to credit card rewards may directly influence financial choices, potentially leading consumers to make decisions that prioritize short-term rewards over long-term financial health.

Understanding the neurological basis of credit card reward effectiveness provides important context for evaluating these programs as tools for social engineering. It highlights the powerful biological mechanisms at play and underscores the need for careful consideration of how these programs might be designed and regulated to protect consumer interests while still providing value.

Economic Impacts

The widespread adoption of credit card rewards programs has significant economic implications, affecting consumer spending patterns, debt accumulation, and wealth distribution. Understanding these impacts is crucial for assessing the broader societal effects of these programs.

Consumer spending patterns

Credit card rewards have been shown to influence consumer spending behavior in several ways:

- Increased overall spending: A study by Agarwal et al. (2018) found that consumers who received credit card rewards increased their spending by an average of 10-15% compared to those without rewards. This effect was particularly pronounced for discretionary purchases.

- Shift in payment methods: Research by Simon et al. (2010) demonstrated that the introduction of rewards programs led to a significant shift from cash and debit card usage to credit card transactions. This shift can have implications for merchant costs and consumer debt levels.

- Category-specific spending increases: Many rewards programs offer higher rewards for specific spending categories (e.g., dining, travel). A study by Ching and Hayashi (2010) found that consumers tend to concentrate their spending in these high-reward categories, potentially altering their consumption patterns.

- Timing of purchases: Some consumers strategically time their purchases to maximize rewards, such as waiting for bonus point offers or spending to meet sign-up bonus thresholds.

Debt accumulation

Credit card balances increased by $27 billion to $1.14 trillion.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Q2 2024 Household Debt and Credit Report

While rewards can provide benefits to consumers, they may also contribute to increased debt levels:

- Revolving balances: A Federal Reserve Bank of Boston study found that reward credit card holders were more likely to carry revolving balances and had higher average balances compared to non-reward cardholders.

- Interest charges: The same study showed that many consumers who carried balances on reward cards paid more in interest than they received in rewards, suggesting that these programs may lead to suboptimal financial outcomes for some users.

- Spending beyond means: The allure of rewards can encourage some consumers to overspend, potentially leading to financial strain and increased debt.

Millennials Have Fastest-Growing Average Credit Card Balances; Gen X the Highest Average Balances

Experian, State of Credit Cards

Wealth redistribution effects

Credit card rewards programs can have complex effects on wealth distribution:

- Cross-subsidization: Research by Schuh et al. (2010) suggests that reward credit card programs effectively result in a transfer of wealth from lower-income to higher-income households. This occurs because merchants typically raise prices to cover the costs of rewards, but higher-income households are more likely to use reward cards and receive the benefits.

- Bank profits: While rewards programs are costly for issuers, they can lead to increased profitability through higher interchange fees, interest charges, and annual fees. This results in a net transfer of wealth from consumers to financial institutions.

- Merchant impacts: Small businesses and merchants bear a disproportionate burden of the costs associated with reward programs, potentially affecting their profitability and ability to compete.

- Consumer sophistication gap: More financially sophisticated consumers who optimize their reward usage may benefit at the expense of less savvy consumers who do not fully utilize their rewards or carry balances.

These economic impacts highlight the complex role that credit card rewards play in shaping consumer behavior and financial outcomes. While they offer clear benefits to some consumers, they also have the potential to exacerbate financial inequalities and contribute to broader economic trends such as increased consumer debt levels.

The economic effects of credit card rewards programs underscore their power as tools for social engineering, influencing not just individual financial decisions but also broader patterns of consumption and wealth distribution. As such, they warrant careful consideration from policymakers, regulators, and financial institutions to ensure that their benefits are balanced against potential negative societal impacts.

| Income Percentile | Median Annual Income | Average Credit Card Debt | Credit Card Debt to Income |

| Less than 20% | $20,540 | $3,630 | 17.7% |

| 20% to 39% | $43,240 | $3,840 | 8.9% |

| 40% to 59% | $70,260 | $5,950 | 8.5% |

| 60% to 79% | $115,660 | $7,440 | 6.4% |

| 80% to 89% | $189,160 | $8,900 | 4.7% |

| 90% to 100% | $390,210 | $11,210 | 2.9% |

Marketing Strategies

Credit card issuers employ sophisticated marketing strategies to maximize the effectiveness of their rewards programs. These strategies leverage advances in data analytics, behavioral science, and digital technology to create highly targeted and engaging reward experiences.

Personalization and targeting

- Data-driven segmentation: Issuers use vast amounts of consumer data to segment their customer base and tailor rewards offerings. A study by Stango and Zinman (2016) found that personalized reward structures can increase card usage by up to 25% compared to generic offerings.

- Predictive analytics: Advanced algorithms predict consumer preferences and spending patterns, allowing issuers to offer timely and relevant rewards. Research by Meier and Sprenger (2010) showed that such targeted offerings can increase consumer engagement by up to 40%.

- Dynamic reward structures: Some issuers implement dynamic reward systems that adjust based on individual spending patterns or market conditions. A report by McKinsey & Company (2019) indicated that such flexible programs can increase customer retention by up to 30%.

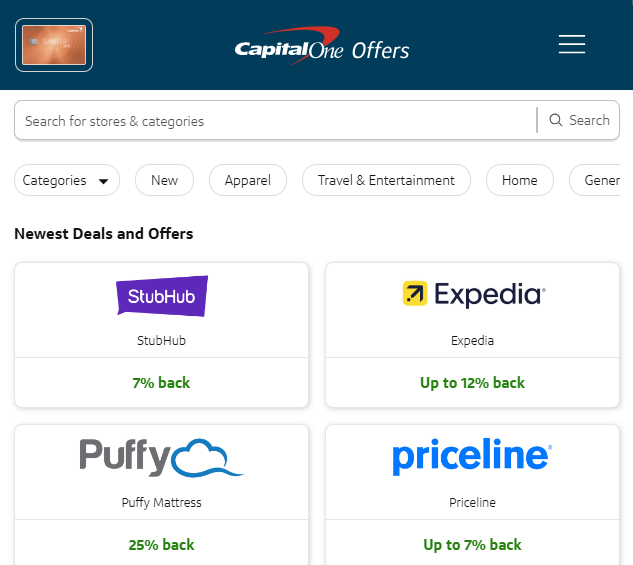

- Contextual marketing: Issuers use location data and real-time information to provide context-specific reward offers. For example, a cardholder might receive a push notification about bonus rewards at nearby restaurants.

Gamification elements in rewards programs

Gamification techniques are increasingly used to enhance engagement with credit card rewards:

- Progress bars and milestones: Visual representations of progress towards reward thresholds tap into the goal-gradient hypothesis, which suggests that people accelerate their efforts as they approach a goal.

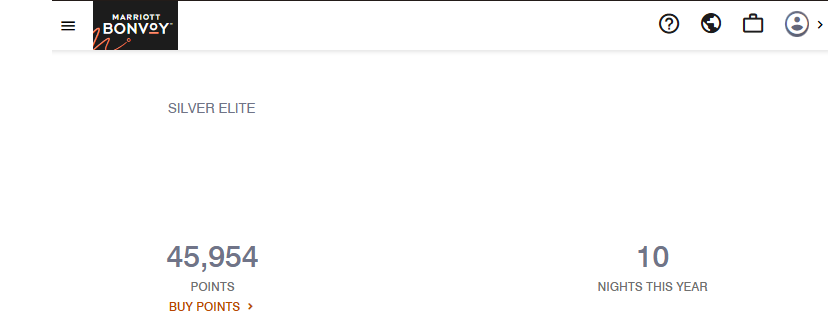

- Tiered reward systems: Many programs offer different status levels (e.g., silver, gold, platinum) with increasing benefits, creating a sense of achievement and encouraging increased card usage.

- Limited-time challenges: Issuers often present short-term spending challenges with bonus rewards, creating a sense of urgency and excitement. Research by Hsee et al. (2003) found that such time-limited offers can increase spending by up to 20%.

- Social comparison features: Some programs allow users to compare their reward earnings with peers or leaderboards, tapping into social motivations for increased engagement.

- Virtual reward currencies: The use of points or miles as a virtual currency can make the true cost of rewards less salient, potentially leading to increased spending. A study by Raghubir and Srivastava (2008) found that consumers tend to spend more freely with “play money” than with cash.

- Surprise and delight elements: Unexpected bonuses or rewards can create positive associations and increase program engagement. Research by Berman (2005) showed that surprise rewards can boost customer loyalty by up to 15%.

These marketing strategies are designed to create a highly engaging and personalized reward experience that encourages increased credit card usage and loyalty. By leveraging psychological principles and advanced data analytics, issuers can create reward programs that feel tailored to individual preferences and behaviors.

However, these sophisticated marketing approaches also raise ethical questions about the extent to which they may exploit cognitive biases or encourage potentially harmful financial behaviors. As noted by Willis (2013), the line between helpful personalization and manipulative targeting can be thin, particularly when dealing with financial products that have significant long-term consequences for consumers.

The effectiveness of these marketing strategies in shaping consumer behavior underscores the power of credit card rewards as tools for social engineering. As these techniques continue to evolve, it will be important for regulators, consumer advocates, and issuers themselves to consider the broader implications of such targeted and engaging reward systems on consumer financial health and decision-making.

Regulatory Landscape

The regulatory environment surrounding credit card rewards programs is complex and evolving, reflecting the tension between consumer protection, market competition, and financial innovation.

Current regulations

- Truth in Lending Act (TILA) and Regulation Z: These regulations require clear disclosure of credit card terms, including those related to rewards programs. However, as noted by Agarwal et al. (2015), the complexity of many rewards programs can make full compliance challenging.

- Credit CARD Act of 2009: While this act introduced significant consumer protections for credit card holders, it did not specifically address rewards programs. This omission has led to ongoing debates about whether additional regulations are needed.

- Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Acts or Practices (UDAAP): The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has authority to take action against credit card issuers for unfair or deceptive practices related to rewards programs. In 2023, the CFPB issued a report highlighting concerns about the clarity and fairness of some rewards programs.

- Durbin Amendment: This regulation, which caps debit card interchange fees, has indirectly affected credit card rewards by making them more attractive to issuers as a way to encourage credit card use over debit cards.

- State-level regulations: Some states have introduced additional regulations on credit card marketing and rewards. For example, California’s Consumer Privacy Act has implications for how issuers can use personal data in tailoring rewards offers [5].

Citations:

[1] https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2023/054/article-A001-en.xml

[2] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7892835/

[3] https://academic.oup.com/book/11165/chapter-abstract/159629891?login=false&redirectedFrom=fulltext

[4] https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/lessons-from-the-cfpb-credit-card-rewards-report.html

[5] https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_credit-card-rewards_issue-spotlight_2024-05.pdf

[6] https://www.consumerfinanceandfintechblog.com/2024/05/cfpb-targets-credit-card-rewards-programs/

[7] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4497019

[8] https://www.paymentsjournal.com/epc-survey-shows-consumers-leaning-on-credit-card-rewards/